Notes from Workshop 2

Emilia Kilpua

The SWATNet Workshop 2 “How to manage a research project” was organized by KU Leuven and Maria Curie-Skłodowska University. Our project manager Anastasiya Boiko had a big role in planning the schedule and in searching for speakers. In addition to some SWATNet beneficiaries and partners (Jan Depauw/SAS) giving presentations, we had several excellent external speakers: Peter Musschoot from Mind the Solution, Veerle Van den Eynden, Sarah De Baets and Barbara Perri from KU Leuven, and ESA Technology broker Pedro Lacerda.

It was a hectic training event, but very informative! Topics covered organization, planning, communication, working in a project, funding prospects and proposal writing.

Lessons learned were far too many to summarise them all, but below are some scattered thoughts I collected during the workshop.

PhD is a project

First of all, a PhD is a project. Many things that are useful in managing bigger projects help also in working towards your thesis. In other words, learning about project management during your PhD is not only useful in some distant future, but right away.

For example, make a Gantt chart for your PhD.

On the other hand, there has to be room for flexibility as you cannot plan science too strictly. Unexpected things will happen. Techniques you initially planned to use may not work, results are unclear, or you will make some unexpected intriguing finding that calls for alternative approaches.

Tell a story

Writing proposals is unavoidable in academia. Start practicing it already during your PhD.

There are several grant opportunities for PhD students, including foundations granting money for conferences and research visits, awards, and grants for observation (e.g., ESO) and computer (e.g., PRACE) time. Maybe you can also contribute to writing proposals within your research group.

For postdoctoral research there are several funding prospects, for example Marie Curie fellowships, ESA’s postdoctoral Research Fellowship, and Jack Eddy fellowship. You can apply these even before you you officially finish your PhD.

Here is a collection of some advices on how to write a proposal

- Read the call and make sure you target your proposal according to that

- Do not work in isolation. Ask for feedback. Discuss with your colleagues and peers.

- Don’t write too technical or specific

- Tell a story. Your proposal needs to entice the reviewers. If something does not fit your story, try to remove it.

- Have a clear goal and address global/diverse issues (i.e. don’t be too narrow)

- Provide facts and show data and preliminary results to support your idea

- Don’t be afraid of rejection, that happens to all of us.

Communication is the key

A point that was brought to the center on many occasions during the workshop was communication. Research is often considered to be all about hard-skills, but soft-skills are almost as important.

Establishing good communication is a usual stumbling stone in projects both in academia and in the private sector.

Good communication builds on self-knowledge. You need to first reflect on what kind of ‘communicator’ you are (analytical, intuitive,..) and how you prefer to communicate (e.g., how frequently you would like to meet with your supervisor). Then share this information with the other person and inquire about their preferences.

Other useful tips:

- If you notice that things are not working, speak up.

- Discuss expectations and avoid making assumptions.

- Set clear roles for the project participants so they know how to best contribute.

- If you need to give criticism do it in a positive manner that does not raise the defense of the other. Avoid using words such as ‘never’/’always’

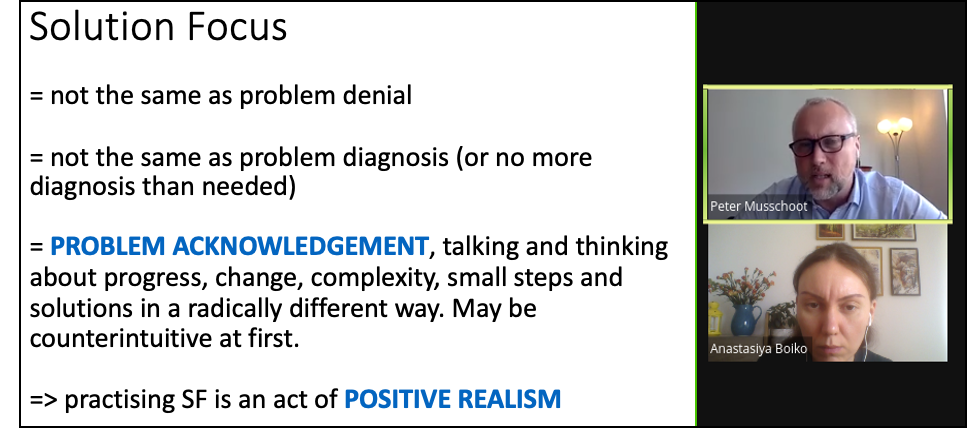

- When someone has a complex problem try to apply Solution Focus rather than problem solving, i.e., help the other person to visualize the desired change and create the solution together (“leading from behind”)

- Focus on positive things/things that are working and those that can be affected

How to manage your time

Nowadays things are more scattered. Doing Phd is not only about research, but systematically focused on developing work-life, interpersonal, outreach and networking skills. How to manage?

Some tips given for time management:

- You cannot do everything perfectly. It is of course good to aim at doing things well, but trying to excel in all aspects leads only to exhaustion.

- Learn to separate things to those you can affect and those you cannot. There is no point to worry or spend time on the latter.

- Do not underestimate the time needed for different tasks. Eg. If you need 3 weeks of full days to write a proposal, plan when you need to start based on how much you can spend each day.

- Keep open spaces in your schedule. It is the same principle as with your desk drawers. If you want to keep them (or your life) in order, fill them a maximum of two-thirds.

- Organize your day so that you focus on a certain thing for longer periods, rather than trying to do everything at once.

- For those things you enjoy less, allocate a specific time and try to do them effectively.

- If you get stuck, do something. E.g., go for a walk.

Benefits of Data Management

Preparing a Data Management plan may sound boring, but there are many benefits. For example, in a project it helps to see connections between how different teams use the data.

Regarding PhD work, many students produce their own data sets (e.g., collection of processed solar images) and codes. It is good to consider making these public, e.g., through different data repositories or GitHub. They can be useful for the wider community and you will get a concrete credit for the work. And it does not always have to be an extensive code. If you used it to make a publication, it is quite likely that someone else finds its also useful.

A nice idea that came from Veerle Van den Eynden was that in a big consortium like SWATNet each sub-project could make its own “mini data management plan”. These are then easy to incorporate into a joint data plan and see the linkages.

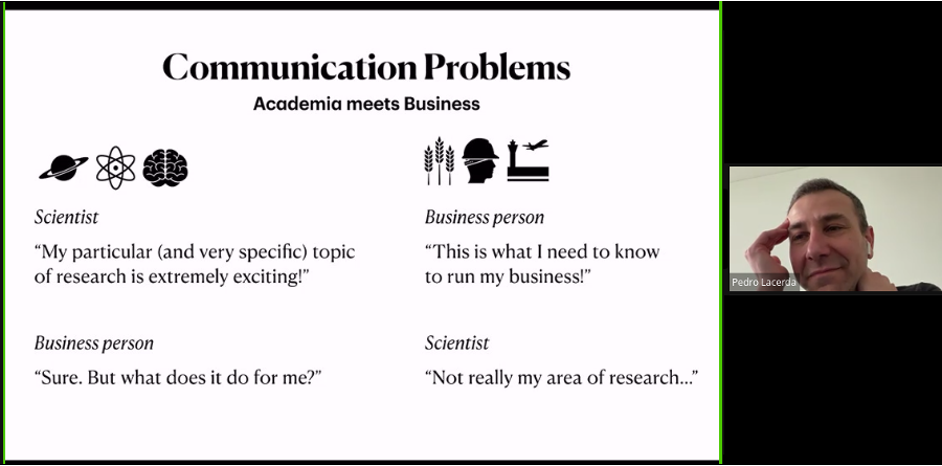

When academy meets business

Combining science and business is not painless. These are two different worlds where people communicate in a different manner and money plays a different role.

Scientific research starts from curiosity and urge to solve problems, while in business the starting point is always the customer and their needs. Also constraints and metrics of success are different.

Business projects can be divided into waterfalls and agile projects. Waterfall is a linear approach that cascades from the requirements through designing, development, and delivering to maintaining. Agile projects instead use a cyclic approach where requirements constantly drive designing, testing, development and delivery. Science projects are typically a combination of these.

It is important to familiarize yourself with both worlds. In the end, both try to find tools to do things they consider important.